http://www.amosauto.com/Articles/Genera ... tunnelport

The pushrods ran right through these tubes, which allowed for much larger ports.

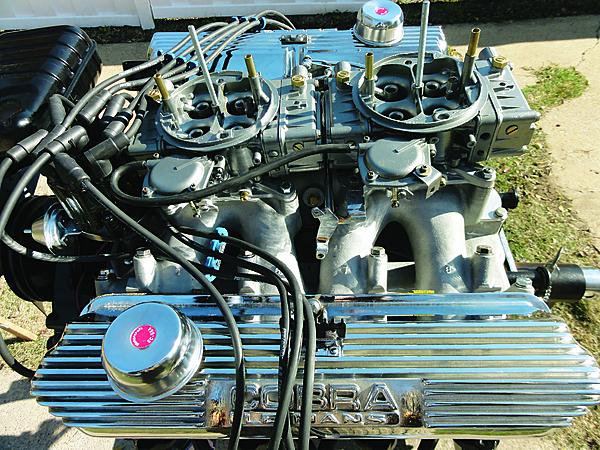

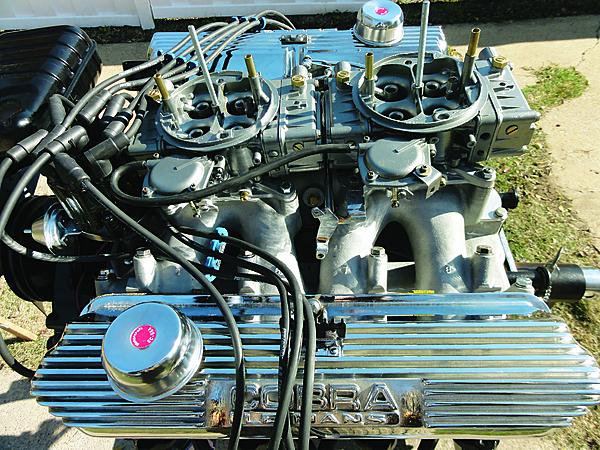

“Skip†Jones had a great time building “his†engine one more time!

The chambers were fully machined by Ford and contained 2.25-inch intakes and 1.73â€-inch sodium-filled exhaust valves.

The bottom end of the 427 engines includes an incredibly strong deep-skirt block design with cross-bolted main caps. This one was cast 2/13/68. Specifically machined spacers that fit between the block and main caps were employed on the cross-bolts. Each of these is hand-etched denoting its position. Due to high water pressures encountered during racing, screw-in freeze plugs were employed. A strong foundation is the difference between finishing a long distance race and being towed back to the pits.

It’s 1968, and if you’re a diehard Ford fan, you’re watching David Pearson and Cale Yarborough dominate NASCAR in their new Mercury Cyclones and Ford Torinos with the killer 427 Tunnel Port bolted under the hood of those long aerodynamic bodies.

The once-feared Hemis struggle all year to keep up and when it’s all over, David has nailed the 1968 championship with 16 wins.

The Tunnel Port phenomenon was the result of a myriad of dynamics throughout the early ’60s when Ford’s Galaxies waged war on the high banks powered by their Low Riser and Medium Riser 427s. The “Riser†moniker refers to the height of the intake manifold and the intake ports of the various cylinder heads that accompanied them. Things got out of hand in 1963 when Chevrolet’s 409s were replaced with the 427 “Mystery Motor†and then the Hemis made their debut at Daytona in 1964. There was immediately a new standard that found the other OEMs working late nights to catch up because they realized, even then, that the power is in the heads and these were just incredible for the day.

Ford’s next evolutionary approach was dubbed the “Hi-Riser†(pretty original huh?), but they were disallowed after the 1964 season when NASCAR determined that engines needed to fit under a flat hood, which the Hi-Riser’s raised ports and tall intake wouldn’t. Those killers went on to terrorize the drag strips in the bubble-hooded Thunderbolts. Then came the “over the top†427 Single Overhead Cam (SOHC) “Cammer†in 1965 with a set of great flowing heads utilizing a single overhead cam on each bank on top of the same basic 427 cross-bolted short block that had proven itself as a reliable high rpm champion.

Can you imagine the look on everyone’s face when that thing showed up? Once again, NASCAR wasn’t buying in since it wasn’t a production engine. But Ford hung in there and unleashed the “Cammer†on the Top Fuel, A/FX and Pro Stock ranks where it earned legendary status. Though they still did very well, Ford was quite frustrated to be forced to compete with the old Medium Riser setups in NASCAR, especially since Mopar had been running the race Hemis for years without ever having installed them in a production car! Ford factory support dropped drastically.

It wasn’t long before everyone realized that it’s not good for the fans (ticket sales) or OEMs (car sales) if there isn’t some serious Big Three racing on the big ovals every weekend, so NASCAR and Ford got together one more time to work out a compromise and thus spawned the Tunnel Port.

Ford knew they had a killer intake port design in the SOHC 427. The overhead cam layout allowed for a huge intake port without the physical placement of a pushrod getting in the way. To create the Tunnel Port head in 1966, an expedient solution was to use the basic SOHC port design and then make it work by pressing a metal tube directly through the center of the intake manifold port to encase the intake pushrod. This idea was also used by Pontiac on their Ram Air V race engines and Ford even resurrected the idea years later with the SVO 351 Tunnel Port heads.

While surely not the best for airflow, it allowed Ford to get back into serious racing quickly. The first versions didn’t actually improve power much over the old Medium Riser racing versions, but with a few revisions they really came alive. To sweeten the pot, NASCAR even allowed Ford to run 2x4s in 1968 instead of the single four-barrel that others were using. With just a few upgrades, all of this was bolted to the same basic 427 short block design once again and these engines went on to be very strong winners into the 1969 season and beyond.

Later, the infamous Boss 429 would make its debut, but they still had to produce those 500 Boss 429 Mustangs to get it homologated for racing. In fact, at the 1969 Daytona 500, NASCAR determined that the build quota for the Boss 429’s hadn’t been met and Tunnel Ports were installed in the Talladegas the night before the race! One of them powered Lee Roy Yarbrough to the win, beating all those pesky Hemis once again!

As is still common today, “last year’s†NASCAR engines were often sold at the end of the season. The shop of John Holman and Ralph Moody was the prime source of everything to do with Ford Racing in the ’60s and did much of the development work on the engines as well as the cars for various teams. One team in particular was the infamous Wood Brothers, who sponsored David Pearson and Cale Yarborough to all those victories.

With all that history behind us, let’s meet J.C. “Skip†Jones. Skip was a well-known engine builder and drag racer in the Virginia area who saw no reason to “re-invent the wheelâ€. He used this annual engine sale six times over the years to score some of the best engines available for his own toys. At the end of the 1968 season, Skip made the trip to the Holman-Moody shop in Charlotte, North Carolina, to purchase an unassembled engine package from the Holman-Moody/Wood Brothers program.

The way it worked was that H-M would magnuflux, measure and inspect all the pieces and sell you a “ready to assemble†Tunnel Port engine. You could also select from various cam/intake/carb choices to tailor it to your needs. Now of course you could also buy these pieces directly over any Ford parts counter, but that didn’t include any proven H-M magic dust that might have been sprinkled on the parts. Since they were unassembled, they weren’t officially complete H-M race engines, but all you had to do was screw it together because everything was already done for you.

Skip first dropped his Tunnel Port into a ’61 Galaxie drag car to compete in local as well as national events, but even in race trim, the Galaxie weighed 4,200 pounds and soon a lightened ’67 Mustang with fiberglass and Lexan throughout and a top-loader four-speed in front of 5.43 gears was showing the Tunnel Port’s true capabilities. Elapsed times in the 10.60-second range were extremely strong in the early ’70s for a car that still managed street duty for some late night “unsanctioned†back road racing encounters. Other than a cam swap (milder) along the way, the engine remained as delivered.

In 1976 the car and engine were sold to David “Sling†Patterson in Phoenix who transplanted the Tunnel Port, untouched, into his ’67 GT500 Shelby Mustang. It was actually run very little until 2006 when Victor Cotto purchased it from “Sling†with plans to find a perfect home for it.

That brings us to the chance encounter between Victor and myself since Victor works for an airline and I travel a lot. He began telling me about this genuine Holman-Moody NASCAR Tunnel Port 427 that had a pedigree linking it to the Wood Brothers Racing Team. Wow … but then I’m thinking … uh huh … yeah, right! Then he produced pictures and I was hooked! Soon after, Victor allowed me to see the engine in person since we live in the same area.

I wasn’t prepared for my own drooling as I stared at the literal racing engine time capsule. During disassembly, every single part was saved, categorized and preserved and then it was verified, measured and magnafluxed by noted FE builder Charles Eller. Together, Victor and I hatched a plan to put it back together using all the original parts, replacing only what we had to, and then put it through a series of dyno tests to see what these engines really did back in the day. We know they were fast but just how much horsepower did they really make? With an engine as virgin as this one, there was no better candidate to learn from!

The search for parts wasn’t too terrible, even though these engines did use some unique components. For example, the original forged pistons used 1/16-inch compression rings (normal race stuff today-rare in ’68) and 1/8-inch low tension oil rings (very uncommon today; most use 3/16-inch on race engines). But Total Seal came to the rescue with a set of plasma moly coated ductile iron rings, part number CR 7155-5. The exhaust valves on these engines had sodium filled stems for cooling (often described as an “elegant solution to a non-existent problemâ€) which are known to corrode from within over time and could easily snap a head off as soon as we fired it up.

For safety, we replaced all the valves with Manley Severe-Duty stainless steel pieces while maintaining the original 2.25-inch intake and 1.73-inch exhaust specifications. Also for safety, we exchanged the aluminum valve spring retainers (trick stuff in 1968) for some upgraded steel ones from Lunati.

Federal-Mogul had the bearings and high pressure oil pump we needed and we also went to a Milodon oil pan, windage tray and pickup assembly. The original pan included well-placed oil baffles and a windage tray also, but it had become pretty beat up over the years. With the deep skirt of the FE block design, we felt that the use of the new pan arrangement would function at least as well as the original and we were confident that everything would be oiled properly.

We were missing the ignition system, so we installed a Pertronix Flamethrower distributor, matching coil and 8mm wires and Victor had the Holley 715 cfm carbs freshened locally. I was curious what the heads actually flowed, so I contacted none other than Darin Morgan at Reher-Morrison Racing Engines to test them on their SuperFlow 600 flowbench. For the day, the results are pretty impressive!

Victor had remained in contact with Skip over the years and when he heard “his†engine was going to be brought back to life, 74-year-old Skip insisted that he get a chance to build it one more time! So, Victor loaded up everything and drove from Texas to Virginia to spend a few great days reliving stories of the Tunnel Port’s heyday and observing the care and skill that Skip put into making this piece of Ford history sing again.

When completed, the old Warhorse took the van ride back to Texas (probably the slowest in its life!) to be strapped to the SuperFlow 902 dyno at the School of Automotive Machinists in Houston, Texas. Owners Judson and Linda Massengill, along with instructor Chris Bennett, have always been great to work with and there was an air of excitement as we unloaded the engine. Soon, some of the SAM students were all over it installing the headers, verifying the 2x4s were opening properly, and hooking up the various lines, hoses and sensors while the rest gathered around to see something they had only heard about since it was history long before most of them were even born.

Judson snapped pictures and sent them to friends like Robert Yates (of Yates Racing fame) since Robert had worked at Holman-Moody when these engines were top dog. In fact, rumor has it that Robert was the builder of the last-minute Tunnel Port that went into the Wood Brothers car at Daytona in ’69!

Before lighting it off, we pulled the distributor to prime it one more time with Royal Purple Break-In oil to protect all the vitals and to make sure that 40-plus year old solid flat-tappet cam combination had no risk of damage. It obviously wasn’t going to need breaking in, but we weren’t taking any chances with a piece of history like this. With 100 octane in the fuel cell to support the 12-plus to one compression ratio, we hit the starter switch which gave us an immediate taste of a high compression motor using the relatively small Ford “B†cam with 242º at .050-inch and .525-inch lift on a tight 108º LSA. It was all the dyno starter could do to turn it over!

But WOW! When it lit, did it sound wicked! I’m talking hard hitting, header crackling, instant throttle response, make your head spin, visceral sounds! You could close your eyes and easily transport yourself to what it must have been like to hear these things rumbling up pit road at Daytona and Talladega.

We weren’t too sure if the timing pointer had been exactly degreed to the balancer, so we started with a very conservative 32° of timing as Chris varied the rpm between 2,000 and 3,000 with a light load on the dyno to seat the rings. Next, a few short sweeps from 4,000 to 5,000 rpm verified all was healthy and it was time to make our first full pull. None of us really knew how much horsepower to expect, but a dyno control room full of spectators were ready to find out. Chris took the helm and laid into the throttle handle hard as we all watched the dyno screens with one eye and the Tunnel Port with the other. The engine took the load but didn’t quite sound as strong as we hoped. When the screen displayed only 339.7 hp at 5,800 rpm, silence fell over the whole room.

We double checked everything and then tried 34° timing and then bumped it to 37º. Things sounded much crisper but we were still only making 379.3 hp at 5,900 rpm. We dialed in two more degrees to get it to 384 hp at 5,900 rpm. At this point, the engine was working hard enough that we could hear some distinct stumbles in the carbs as it progressed through the test. Not terrible, but definitely not as healthy-sounding as they should be. We decided to pop the valve covers and re-lash the valves, pull some plugs and check everything over.

All was good, so we bumped the timing to an indicated 41° and gained another 14 hp for a max reading of 398.2 hp at 5,900 rpm and 398.7 lbs-ft of torque at 4,300 rpm. We tried two more degrees of timing with an indicated 43° and it responded well by finally breaking the 400 hp hurdle with 413.9 hp at 6,000 rpm and 411 lbs-ft at 4,300 rpm.

We had been watching the vacuum operated secondary linkage on the carbs and they appeared to be working fine, just a little slow. I decided to enact a quick ’60s carb tuning trick and stick screws in the carburetor secondary throttle linkage slots to mechanically open the secondary side of the carbs for the next test. That was a game-changer worth 28 hp and 55 lbs-ft of torque and the screen now displayed 442.5 hp at 5,600 rpm and 466.1 lbs-ft at 4,400 rpm. So far, the only tuning we had done was to bump the timing, which was improving the Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) numbers and showing the engine was operating much more efficiently.

But as we did so, we could all hear those carbs just weren’t right and we knew they were holding the Tunnel Port back. At the time, Victor didn’t want to get too involved in going into the carbs, because frankly who knows what might have been done to them over the years? We would need to go back to ground zero and measure every passageway and correct as needed to sort them out. We made some more pulls to verify our results and with Victor needing to get back home, the day ended with a tight, strong sounding motor that held perfect oil pressure on every pull.

But we were still disappointed in the numbers. I mean how could an engine this trick “only†make 442 hp? Is that all they really had in them? I crunched the numbers and using the 2,800-pound race weight that Skip said his Mustang weighed, I saw that if you had 500 hp you could run 10.60s. Knowing that Skip liked to “wind it to the moon†and with the steep gears he was using, it all sounded possible.

Skip also told us that at first he used one of the other Holman-Moody solid flat tappet drag race “D†cams with 260º at .050-inch of duration and .607-inch lift. Surely that would have raised the rpm range up to where those huge heads really wanted to run. Remember, this was a NASCAR superspeedway engine designed to run wide-open all day long. No one was worried about what it did under 6,000 rpm.

I asked Victor if he wanted to get another cam and make it really come alive with another dyno session and some serious tuning. He thought for a while, but he really wanted to pay tribute to the legacy that Skip had created and decided to stick with the current cam to make it more tractable on the street.

But hold on, we’re not done yet! Victor couldn’t stand it very long. He KNEW there had to be more in it and contacted noted builder Ted Eaton at Eaton Balancing to conduct another dyno session. One big advantage is that Ted really loves old Fords and has plenty of extra parts to test with. This time those carbs were going to produce or else!

After installing the Tunnel Port on the dyno with some much improved “race†headers instead of the street headers we had used previously, Ted checked things over and gave everything a clean bill of health. A compression test verified 230 pounds of cranking compression and the need for race fuel. He double-checked the valves, and made the first pull that pretty much mirrored the last session at SAM even though Ted uses a DTS dyno instead of a SuperFlow 902. Next came quite a bit of carburetor tuning that still found things not quite right. The issue was isolated to the secondary side of the carbs and Ted decided to disconnect the secondaries completely and continue tuning.

Still not satisfied with how they performed, eventually 495 hp at 6,000 rpm and 474 lbs-ft at 4,900 rpm came out of the original carbs. At this point the temptation was too great and Victor caved in to allow Ted to install a set of custom-calibrated 780 cfm Holleys that he knew worked correctly. The instant it fired, he knew he was on the right path with a completely different sound and a tingle in the air.

When the trigger was pulled, the infamous Tunnel Port finally came into its own with a clean, crisp howl that produced 546 hp at 6,000 rpm and 516 lbs-ft at 5,000 rpm! Can you believe an over 100 hp gain from some better headers and some carb swapping? Now I really wanted to stick one of those Holman-Moody 260° at .050-inch “Drag Race†cams in there and let it scream! If you ever had doubts as to the value of a good dyno tuning session, this project should help you justify the cost for sure!

The 427 Tunnel Port is an iconic piece of Ford and NASCAR history. Our testing proves it was easily capable of 575-plus hp, maybe even near 600 hp if you spin it high enough. The reputation it has as a winning racing engine as well as a killer street beast for the hardcore types is well earned and deserved. If you want to take a trip back to the 1968 Daytona 500, go to http://youtu.be/NWdXmTI56V4 and turn up the volume on your computer. Close your eyes and you’ll be transported to a seat right on the fence!

The pushrods ran right through these tubes, which allowed for much larger ports.

“Skip†Jones had a great time building “his†engine one more time!

The chambers were fully machined by Ford and contained 2.25-inch intakes and 1.73â€-inch sodium-filled exhaust valves.

The bottom end of the 427 engines includes an incredibly strong deep-skirt block design with cross-bolted main caps. This one was cast 2/13/68. Specifically machined spacers that fit between the block and main caps were employed on the cross-bolts. Each of these is hand-etched denoting its position. Due to high water pressures encountered during racing, screw-in freeze plugs were employed. A strong foundation is the difference between finishing a long distance race and being towed back to the pits.

It’s 1968, and if you’re a diehard Ford fan, you’re watching David Pearson and Cale Yarborough dominate NASCAR in their new Mercury Cyclones and Ford Torinos with the killer 427 Tunnel Port bolted under the hood of those long aerodynamic bodies.

The once-feared Hemis struggle all year to keep up and when it’s all over, David has nailed the 1968 championship with 16 wins.

The Tunnel Port phenomenon was the result of a myriad of dynamics throughout the early ’60s when Ford’s Galaxies waged war on the high banks powered by their Low Riser and Medium Riser 427s. The “Riser†moniker refers to the height of the intake manifold and the intake ports of the various cylinder heads that accompanied them. Things got out of hand in 1963 when Chevrolet’s 409s were replaced with the 427 “Mystery Motor†and then the Hemis made their debut at Daytona in 1964. There was immediately a new standard that found the other OEMs working late nights to catch up because they realized, even then, that the power is in the heads and these were just incredible for the day.

Ford’s next evolutionary approach was dubbed the “Hi-Riser†(pretty original huh?), but they were disallowed after the 1964 season when NASCAR determined that engines needed to fit under a flat hood, which the Hi-Riser’s raised ports and tall intake wouldn’t. Those killers went on to terrorize the drag strips in the bubble-hooded Thunderbolts. Then came the “over the top†427 Single Overhead Cam (SOHC) “Cammer†in 1965 with a set of great flowing heads utilizing a single overhead cam on each bank on top of the same basic 427 cross-bolted short block that had proven itself as a reliable high rpm champion.

Can you imagine the look on everyone’s face when that thing showed up? Once again, NASCAR wasn’t buying in since it wasn’t a production engine. But Ford hung in there and unleashed the “Cammer†on the Top Fuel, A/FX and Pro Stock ranks where it earned legendary status. Though they still did very well, Ford was quite frustrated to be forced to compete with the old Medium Riser setups in NASCAR, especially since Mopar had been running the race Hemis for years without ever having installed them in a production car! Ford factory support dropped drastically.

It wasn’t long before everyone realized that it’s not good for the fans (ticket sales) or OEMs (car sales) if there isn’t some serious Big Three racing on the big ovals every weekend, so NASCAR and Ford got together one more time to work out a compromise and thus spawned the Tunnel Port.

Ford knew they had a killer intake port design in the SOHC 427. The overhead cam layout allowed for a huge intake port without the physical placement of a pushrod getting in the way. To create the Tunnel Port head in 1966, an expedient solution was to use the basic SOHC port design and then make it work by pressing a metal tube directly through the center of the intake manifold port to encase the intake pushrod. This idea was also used by Pontiac on their Ram Air V race engines and Ford even resurrected the idea years later with the SVO 351 Tunnel Port heads.

While surely not the best for airflow, it allowed Ford to get back into serious racing quickly. The first versions didn’t actually improve power much over the old Medium Riser racing versions, but with a few revisions they really came alive. To sweeten the pot, NASCAR even allowed Ford to run 2x4s in 1968 instead of the single four-barrel that others were using. With just a few upgrades, all of this was bolted to the same basic 427 short block design once again and these engines went on to be very strong winners into the 1969 season and beyond.

Later, the infamous Boss 429 would make its debut, but they still had to produce those 500 Boss 429 Mustangs to get it homologated for racing. In fact, at the 1969 Daytona 500, NASCAR determined that the build quota for the Boss 429’s hadn’t been met and Tunnel Ports were installed in the Talladegas the night before the race! One of them powered Lee Roy Yarbrough to the win, beating all those pesky Hemis once again!

As is still common today, “last year’s†NASCAR engines were often sold at the end of the season. The shop of John Holman and Ralph Moody was the prime source of everything to do with Ford Racing in the ’60s and did much of the development work on the engines as well as the cars for various teams. One team in particular was the infamous Wood Brothers, who sponsored David Pearson and Cale Yarborough to all those victories.

With all that history behind us, let’s meet J.C. “Skip†Jones. Skip was a well-known engine builder and drag racer in the Virginia area who saw no reason to “re-invent the wheelâ€. He used this annual engine sale six times over the years to score some of the best engines available for his own toys. At the end of the 1968 season, Skip made the trip to the Holman-Moody shop in Charlotte, North Carolina, to purchase an unassembled engine package from the Holman-Moody/Wood Brothers program.

The way it worked was that H-M would magnuflux, measure and inspect all the pieces and sell you a “ready to assemble†Tunnel Port engine. You could also select from various cam/intake/carb choices to tailor it to your needs. Now of course you could also buy these pieces directly over any Ford parts counter, but that didn’t include any proven H-M magic dust that might have been sprinkled on the parts. Since they were unassembled, they weren’t officially complete H-M race engines, but all you had to do was screw it together because everything was already done for you.

Skip first dropped his Tunnel Port into a ’61 Galaxie drag car to compete in local as well as national events, but even in race trim, the Galaxie weighed 4,200 pounds and soon a lightened ’67 Mustang with fiberglass and Lexan throughout and a top-loader four-speed in front of 5.43 gears was showing the Tunnel Port’s true capabilities. Elapsed times in the 10.60-second range were extremely strong in the early ’70s for a car that still managed street duty for some late night “unsanctioned†back road racing encounters. Other than a cam swap (milder) along the way, the engine remained as delivered.

In 1976 the car and engine were sold to David “Sling†Patterson in Phoenix who transplanted the Tunnel Port, untouched, into his ’67 GT500 Shelby Mustang. It was actually run very little until 2006 when Victor Cotto purchased it from “Sling†with plans to find a perfect home for it.

That brings us to the chance encounter between Victor and myself since Victor works for an airline and I travel a lot. He began telling me about this genuine Holman-Moody NASCAR Tunnel Port 427 that had a pedigree linking it to the Wood Brothers Racing Team. Wow … but then I’m thinking … uh huh … yeah, right! Then he produced pictures and I was hooked! Soon after, Victor allowed me to see the engine in person since we live in the same area.

I wasn’t prepared for my own drooling as I stared at the literal racing engine time capsule. During disassembly, every single part was saved, categorized and preserved and then it was verified, measured and magnafluxed by noted FE builder Charles Eller. Together, Victor and I hatched a plan to put it back together using all the original parts, replacing only what we had to, and then put it through a series of dyno tests to see what these engines really did back in the day. We know they were fast but just how much horsepower did they really make? With an engine as virgin as this one, there was no better candidate to learn from!

The search for parts wasn’t too terrible, even though these engines did use some unique components. For example, the original forged pistons used 1/16-inch compression rings (normal race stuff today-rare in ’68) and 1/8-inch low tension oil rings (very uncommon today; most use 3/16-inch on race engines). But Total Seal came to the rescue with a set of plasma moly coated ductile iron rings, part number CR 7155-5. The exhaust valves on these engines had sodium filled stems for cooling (often described as an “elegant solution to a non-existent problemâ€) which are known to corrode from within over time and could easily snap a head off as soon as we fired it up.

For safety, we replaced all the valves with Manley Severe-Duty stainless steel pieces while maintaining the original 2.25-inch intake and 1.73-inch exhaust specifications. Also for safety, we exchanged the aluminum valve spring retainers (trick stuff in 1968) for some upgraded steel ones from Lunati.

Federal-Mogul had the bearings and high pressure oil pump we needed and we also went to a Milodon oil pan, windage tray and pickup assembly. The original pan included well-placed oil baffles and a windage tray also, but it had become pretty beat up over the years. With the deep skirt of the FE block design, we felt that the use of the new pan arrangement would function at least as well as the original and we were confident that everything would be oiled properly.

We were missing the ignition system, so we installed a Pertronix Flamethrower distributor, matching coil and 8mm wires and Victor had the Holley 715 cfm carbs freshened locally. I was curious what the heads actually flowed, so I contacted none other than Darin Morgan at Reher-Morrison Racing Engines to test them on their SuperFlow 600 flowbench. For the day, the results are pretty impressive!

Victor had remained in contact with Skip over the years and when he heard “his†engine was going to be brought back to life, 74-year-old Skip insisted that he get a chance to build it one more time! So, Victor loaded up everything and drove from Texas to Virginia to spend a few great days reliving stories of the Tunnel Port’s heyday and observing the care and skill that Skip put into making this piece of Ford history sing again.

When completed, the old Warhorse took the van ride back to Texas (probably the slowest in its life!) to be strapped to the SuperFlow 902 dyno at the School of Automotive Machinists in Houston, Texas. Owners Judson and Linda Massengill, along with instructor Chris Bennett, have always been great to work with and there was an air of excitement as we unloaded the engine. Soon, some of the SAM students were all over it installing the headers, verifying the 2x4s were opening properly, and hooking up the various lines, hoses and sensors while the rest gathered around to see something they had only heard about since it was history long before most of them were even born.

Judson snapped pictures and sent them to friends like Robert Yates (of Yates Racing fame) since Robert had worked at Holman-Moody when these engines were top dog. In fact, rumor has it that Robert was the builder of the last-minute Tunnel Port that went into the Wood Brothers car at Daytona in ’69!

Before lighting it off, we pulled the distributor to prime it one more time with Royal Purple Break-In oil to protect all the vitals and to make sure that 40-plus year old solid flat-tappet cam combination had no risk of damage. It obviously wasn’t going to need breaking in, but we weren’t taking any chances with a piece of history like this. With 100 octane in the fuel cell to support the 12-plus to one compression ratio, we hit the starter switch which gave us an immediate taste of a high compression motor using the relatively small Ford “B†cam with 242º at .050-inch and .525-inch lift on a tight 108º LSA. It was all the dyno starter could do to turn it over!

But WOW! When it lit, did it sound wicked! I’m talking hard hitting, header crackling, instant throttle response, make your head spin, visceral sounds! You could close your eyes and easily transport yourself to what it must have been like to hear these things rumbling up pit road at Daytona and Talladega.

We weren’t too sure if the timing pointer had been exactly degreed to the balancer, so we started with a very conservative 32° of timing as Chris varied the rpm between 2,000 and 3,000 with a light load on the dyno to seat the rings. Next, a few short sweeps from 4,000 to 5,000 rpm verified all was healthy and it was time to make our first full pull. None of us really knew how much horsepower to expect, but a dyno control room full of spectators were ready to find out. Chris took the helm and laid into the throttle handle hard as we all watched the dyno screens with one eye and the Tunnel Port with the other. The engine took the load but didn’t quite sound as strong as we hoped. When the screen displayed only 339.7 hp at 5,800 rpm, silence fell over the whole room.

We double checked everything and then tried 34° timing and then bumped it to 37º. Things sounded much crisper but we were still only making 379.3 hp at 5,900 rpm. We dialed in two more degrees to get it to 384 hp at 5,900 rpm. At this point, the engine was working hard enough that we could hear some distinct stumbles in the carbs as it progressed through the test. Not terrible, but definitely not as healthy-sounding as they should be. We decided to pop the valve covers and re-lash the valves, pull some plugs and check everything over.

All was good, so we bumped the timing to an indicated 41° and gained another 14 hp for a max reading of 398.2 hp at 5,900 rpm and 398.7 lbs-ft of torque at 4,300 rpm. We tried two more degrees of timing with an indicated 43° and it responded well by finally breaking the 400 hp hurdle with 413.9 hp at 6,000 rpm and 411 lbs-ft at 4,300 rpm.

We had been watching the vacuum operated secondary linkage on the carbs and they appeared to be working fine, just a little slow. I decided to enact a quick ’60s carb tuning trick and stick screws in the carburetor secondary throttle linkage slots to mechanically open the secondary side of the carbs for the next test. That was a game-changer worth 28 hp and 55 lbs-ft of torque and the screen now displayed 442.5 hp at 5,600 rpm and 466.1 lbs-ft at 4,400 rpm. So far, the only tuning we had done was to bump the timing, which was improving the Brake Specific Fuel Consumption (BSFC) numbers and showing the engine was operating much more efficiently.

But as we did so, we could all hear those carbs just weren’t right and we knew they were holding the Tunnel Port back. At the time, Victor didn’t want to get too involved in going into the carbs, because frankly who knows what might have been done to them over the years? We would need to go back to ground zero and measure every passageway and correct as needed to sort them out. We made some more pulls to verify our results and with Victor needing to get back home, the day ended with a tight, strong sounding motor that held perfect oil pressure on every pull.

But we were still disappointed in the numbers. I mean how could an engine this trick “only†make 442 hp? Is that all they really had in them? I crunched the numbers and using the 2,800-pound race weight that Skip said his Mustang weighed, I saw that if you had 500 hp you could run 10.60s. Knowing that Skip liked to “wind it to the moon†and with the steep gears he was using, it all sounded possible.

Skip also told us that at first he used one of the other Holman-Moody solid flat tappet drag race “D†cams with 260º at .050-inch of duration and .607-inch lift. Surely that would have raised the rpm range up to where those huge heads really wanted to run. Remember, this was a NASCAR superspeedway engine designed to run wide-open all day long. No one was worried about what it did under 6,000 rpm.

I asked Victor if he wanted to get another cam and make it really come alive with another dyno session and some serious tuning. He thought for a while, but he really wanted to pay tribute to the legacy that Skip had created and decided to stick with the current cam to make it more tractable on the street.

But hold on, we’re not done yet! Victor couldn’t stand it very long. He KNEW there had to be more in it and contacted noted builder Ted Eaton at Eaton Balancing to conduct another dyno session. One big advantage is that Ted really loves old Fords and has plenty of extra parts to test with. This time those carbs were going to produce or else!

After installing the Tunnel Port on the dyno with some much improved “race†headers instead of the street headers we had used previously, Ted checked things over and gave everything a clean bill of health. A compression test verified 230 pounds of cranking compression and the need for race fuel. He double-checked the valves, and made the first pull that pretty much mirrored the last session at SAM even though Ted uses a DTS dyno instead of a SuperFlow 902. Next came quite a bit of carburetor tuning that still found things not quite right. The issue was isolated to the secondary side of the carbs and Ted decided to disconnect the secondaries completely and continue tuning.

Still not satisfied with how they performed, eventually 495 hp at 6,000 rpm and 474 lbs-ft at 4,900 rpm came out of the original carbs. At this point the temptation was too great and Victor caved in to allow Ted to install a set of custom-calibrated 780 cfm Holleys that he knew worked correctly. The instant it fired, he knew he was on the right path with a completely different sound and a tingle in the air.

When the trigger was pulled, the infamous Tunnel Port finally came into its own with a clean, crisp howl that produced 546 hp at 6,000 rpm and 516 lbs-ft at 5,000 rpm! Can you believe an over 100 hp gain from some better headers and some carb swapping? Now I really wanted to stick one of those Holman-Moody 260° at .050-inch “Drag Race†cams in there and let it scream! If you ever had doubts as to the value of a good dyno tuning session, this project should help you justify the cost for sure!

The 427 Tunnel Port is an iconic piece of Ford and NASCAR history. Our testing proves it was easily capable of 575-plus hp, maybe even near 600 hp if you spin it high enough. The reputation it has as a winning racing engine as well as a killer street beast for the hardcore types is well earned and deserved. If you want to take a trip back to the 1968 Daytona 500, go to http://youtu.be/NWdXmTI56V4 and turn up the volume on your computer. Close your eyes and you’ll be transported to a seat right on the fence!